My friend’s daughter, Zoe, came home from school one day and told her dad about something that happened in school. She was in 8th grade at the time, and a trainer had just come to her class to conduct a session on sex ed. She and a boy were asked by the trainer stand in the front of the room and hold two sides of a plastic heart together. One side was blue; the other pink. You can guess which side Zoe was asked to hold. The trainer then told them to pull the heart apart. When the two pieces of plastic were separated, the trainer told the class, “This is what happens when you have sex before marriage. Your heart is broken”.

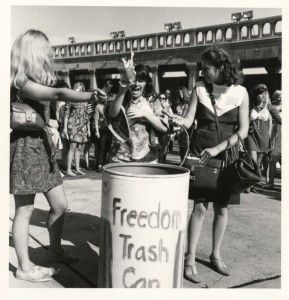

When Zoe got home that day, she told her dad about it and said that it was “kind of ridiculous…stupid”. But she also felt weird about it. And so did her dad. He reached out to other parents he knew at the school, and what ensued – once the word got out – was a year-long campaign to identify who ran the program, how they got into the school in the first place, and ultimately, how to get rid of them. We discovered that the program was run by a non-profit organization called Healthy Futures, which claims it is “dedicated to empowering adolescents to avoid the health, social, and psychological consequences of risky decisions by equipping students with the tools and educated support system they need to make healthy choices”. Their services included – and continue to include – classroom-based education, peer education through after-school and summer programs, parent education workshops, school and community connections, and web-based resources. But when we dug deeper, we discovered that Healthy Futures was an abstinence-only-until-marriage (AOUM) program that was part of a larger entity in Massachusetts called A Woman’s Concern. Healthy Futures is considered “the intervention side” of this larger entity. Neither the website for Healthy Futures or A Woman’s Concern indicate a connection between these two groups. That can be found on a Christian website, listing them as a volunteer opportunity. The mission statement for A Woman’s Concern’s mission is as follows:

A

Woman’s Concern is a Christian mission to women and couples in

pregnancy distress, especially those considering abortion due to lack of

information and support, and dedicated to providing life-saving help in

a life-changing way. To this end we provide competent and caring

services that include free pregnancy tests, sonograms, peer counseling

and intervention, on-going support and referrals, parenting preparation

classes, post-abortion healing and opportunities to learn about healthy

sexual values, mature relationships and how to establish a vital

relationship with Jesus Christ and His Church.

A

Woman’s Concern is a Christian mission to women and couples in

pregnancy distress, especially those considering abortion due to lack of

information and support, and dedicated to providing life-saving help in

a life-changing way. To this end we provide competent and caring

services that include free pregnancy tests, sonograms, peer counseling

and intervention, on-going support and referrals, parenting preparation

classes, post-abortion healing and opportunities to learn about healthy

sexual values, mature relationships and how to establish a vital

relationship with Jesus Christ and His Church. I was in shock. What was a fundamentalist Christian program doing in a public school? And for the next year, I was obsessed with understanding more about this organization and its values, as well as learning about the different approaches to sexuality education. I wanted to understand where Healthy Futures – sponsored in stealth-like fashion by A Woman’s Concern and brought into my daughter’s school – fit along the spectrum of sexuality education curriculum.

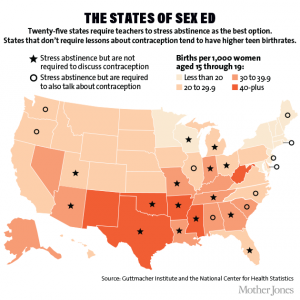

The Case against abstinence-only-until-marriage programs

According to the 35-year-old national program, Advocates for Youth, there are a number of reasons abstinence-only-until-marriage (AOUM) programs don’t work. Of the eleven states that have evaluated the impact of AOUM programs, none have demonstrated a reduction in teen sexual activity. One strategy of these programs is have teens make a “virginity pledge”, promising to remain virgins until marriage. Researchers found that despite their promise, some “pledgers” engage in risky oral or anal sex, and if they do end up having vaginal intercourse, they don’t use condoms.

According to researchers, Hannah Brückner and Peter Bearman, even if virginity pledges help some young people delay sexual activity for up to 18 months, once they break their pledge, they are less likely to use contraception or condoms, which puts them at risk for unintended pregnancy and HIV or other STDs.

AOUM programs often contain lies and inaccurate information. A 2004 report about AOUM programs

says that over 80% of federally-funded AOUM programs contain false

information about the effectiveness of contraceptives, claiming that

condoms aren’t effective in preventing sexually transmitted diseases and

pregnancy. AOUM programs also contain false information about the risks

of abortion, with one curriculum claiming that 5% to 10% of women who

have legal abortions will become sterile, will be more at risk for

giving birth later on to a child with mental retardation, and that tubal

and cervical pregnancies are increased following abortions. AOUM

curricula blurs religion and science, presenting “as scientific fact the

religious view that life begins at conception”. One curriculum calls a

43-day-old fetus a “thinking person”. And AOUM curricula “treat

stereotypes about girls and boys as scientific fact”. The report

concludes that these programs are a colossal waste of federal taxpayers’

dollars.

AOUM programs often contain lies and inaccurate information. A 2004 report about AOUM programs

says that over 80% of federally-funded AOUM programs contain false

information about the effectiveness of contraceptives, claiming that

condoms aren’t effective in preventing sexually transmitted diseases and

pregnancy. AOUM programs also contain false information about the risks

of abortion, with one curriculum claiming that 5% to 10% of women who

have legal abortions will become sterile, will be more at risk for

giving birth later on to a child with mental retardation, and that tubal

and cervical pregnancies are increased following abortions. AOUM

curricula blurs religion and science, presenting “as scientific fact the

religious view that life begins at conception”. One curriculum calls a

43-day-old fetus a “thinking person”. And AOUM curricula “treat

stereotypes about girls and boys as scientific fact”. The report

concludes that these programs are a colossal waste of federal taxpayers’

dollars.The major clearinghouse on sexuality education in the US – The Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS), says AOUM programs are “based on fear and shame, inaccurate and misleading information, and biased views of marriage, sexual orientation and family structure.”

The case for comprehensive sexuality education

According to SIECUS, comprehensive sex education provides students with “medically accurate information about the health benefits and side effects of all contraceptives, including condoms, as a means to prevent pregnancy and reduce the risk of contracting STIs, including HIV/AIDS”. It teaches young people “the skills to make responsible decisions about sexuality, including how to avoid unwanted verbal, physical, and sexual advances”, as well as how “alcohol and drug use can effect responsible decision making”. Students are provided with the tools to make informed decisions. While these programs stress the value of abstinence, they also prepare students for when they become sexually active.

A series of studies

show that the lessons learned in comprehensive sex education programs

are critical for healthy decision making during the teen years and

beyond. When teens are educated about condoms and have access to them,

they’re more likely to use them. When teens practice contraception in

their first sexual relationship, they’re more likely to keep doing so,

compared to those who used either no method or used a method

inconsistently. In fact, a 86% decline in teen pregnancy from 1995 to

2002 is attributed by Columbia University researchers to dramatic

improvements in contraceptive use. Only 14% of the decline in teen

pregnancy rates was attributed to a decrease in sexual activity.

A series of studies

show that the lessons learned in comprehensive sex education programs

are critical for healthy decision making during the teen years and

beyond. When teens are educated about condoms and have access to them,

they’re more likely to use them. When teens practice contraception in

their first sexual relationship, they’re more likely to keep doing so,

compared to those who used either no method or used a method

inconsistently. In fact, a 86% decline in teen pregnancy from 1995 to

2002 is attributed by Columbia University researchers to dramatic

improvements in contraceptive use. Only 14% of the decline in teen

pregnancy rates was attributed to a decrease in sexual activity.Researchers Starkman and Rajani found that one-half of HIV infections in the US and two-thirds of all sexually transmitted diseases (STD) occur among young people under the age of 25. By the end of high school, nearly two thirds of American youth are sexually active, and one in five has had four or more sexual partners. Nonetheless, they say, “Despite these alarming statistics, less than half of all public schools in the United States offer information on how to obtain contraceptives and most schools increasingly teach abstinence-only-until-marriage (or ‘abstinence-only’) education”.

A Short history of Abstinence-only–until marriage programs

Over

the past few decades, the federal government has poured millions of

tax-payer dollars into AOUM programming. The two main federal funding

streams for AOUM programs were the Community-Based Abstinence Education

grant program and the AOUM portion of the Adolescent Family Life Act.

Funding for these unproven programs expanded from 1996 until 2006,

particularly during the Bush Administration. Between 1996 and federal

Fiscal Year 2010, Congress allocated over $1.5 billion tax-payer dollars

into AOUM programs and a significant amount of funding CONTINUES today!

Over

the past few decades, the federal government has poured millions of

tax-payer dollars into AOUM programming. The two main federal funding

streams for AOUM programs were the Community-Based Abstinence Education

grant program and the AOUM portion of the Adolescent Family Life Act.

Funding for these unproven programs expanded from 1996 until 2006,

particularly during the Bush Administration. Between 1996 and federal

Fiscal Year 2010, Congress allocated over $1.5 billion tax-payer dollars

into AOUM programs and a significant amount of funding CONTINUES today!Interestingly, President Bill Clinton’s “welfare reform” bill, signed into law in 1996, included a provision for AOUM programs. This funding, created via Title V, Section 510(b) of the Social Security Act, represented a shift from promoting pregnancy prevention programs to promoting abstinence from sexual activity outside of marriage, at any age. Sex was to be “confined to married couples”, and abstinence from sexual activity outside of marriage became the “expected standard for all school-age children”; with the “exclusive purpose (of) teaching the social, psychological, and health gains to be realized by abstaining from sexual activity”. In other words, these programs could not – still cannot – discuss, much less advocate for the use of contraceptives, except to focus on their failure rates. AOUM programs are meant teach that sexual activity outside of the context of marriage is likely to have “harmful psychological and physical effects”, and that it’s important for people to “attain self-sufficiency before engaging in sexual activity.”

After decades of federal support for a number of these programs, the Obama Administration and Congress eliminated the two main funding streams for AOUM programs. Congress allowed the third funding source, the Title V AOUM program, to expire on June 30, 2009. But this program was unfortunately revived as part of the health care reform package, which continues to provide $50 million a year in mandatory funding to this very day!

Power of the parents…

After discovering the AOUM program at our school, a core of parents initially gathered together and we drew up a petition, calling for the school to remove Healthy Futures and demanding comprehensive sexuality education. The support for the petition was phenomenal. Hundreds of parents signed it! Our main concern was our children’s health. We felt that it was inappropriate for a fundamentalist Christian organization, such as A Woman’s Concern, to be brought into our school. And we didn’t like the sneaky way the school had chosen to bring this program into the school.

We also wanted to know how Healthy Futures had come to our school in the first place. To our surprise, we discovered that the school’s Vice Principal had brought them. He claimed that a parent referred him and that he had no knowledge of the group’s affiliation.

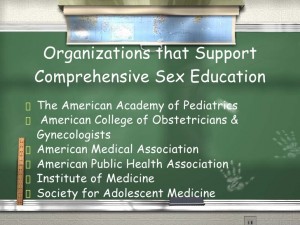

We

presented a statement to the school administration, accompanied by a

list of over 140 organizations that support comprehensive sexuality

education in public schools, stating the following:

We

presented a statement to the school administration, accompanied by a

list of over 140 organizations that support comprehensive sexuality

education in public schools, stating the following:We are concerned that the Healthy Futures curriculum is driven by a very narrow viewpoint and provides inaccurate information regarding the viability of condoms as protection against STDs and unwanted pregnancies. The (school system) has a comprehensive sexuality education curriculum that has served the system well for many years…We believe that it is in the interests of the community served by the (school system) to be given full access to the comprehensive sexuality education curriculum established by the (XX) Public Schools.

We went to dozens of meetings – with parents and administrators – where we presented data on AOUM and comprehensive sexuality education, and we demanded that the Assistant Principal be held accountable. Under duress, he promised to review other options for the following year. We also demanded that parents and students be included in any assessment of alternative options. A number of the parent teacher meetings were very tense, because parents – particularly those who were fundamentalist Christian and anti-abortion – felt personally offended that we were organizing to get rid of this program. We let them know that we respected their points of view, but that a religiously-affiliated program didn’t belong in a public school.

In

the end we won!

In

the end we won! After all our wrangling with the school administration, we realized that we needed to take it one level up, to the School Committee, who shared our shock that a religiously affiliated program had snuck into the school. We also presented our case to the Superintendent of the school district, and as it turned out, his wife was on the Board of Planned Parenthood. Within weeks, the program was eliminated from the district!

With this victory, parents continued to be active in a number of other school-based activities. So, not only were we successful in removing AOUM programming; we also invigorated parent engagement in the school, which spilled over to other efforts to improve the school. I was asked to be on a Sexuality Education Curriculum Committee for the school system, and spent the next year reviewing curriculum which would be brought into the schools. We ended up selecting Planned Parenthood’s excellent comprehensive sexuality education curriculum.

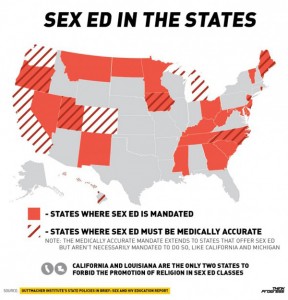

To date, 23 states have rejected Title V abstinence-only federal funding, including: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. This is progress, but the fight isn’t over for other states and school districts. There’s still work to do…

FacebookTwitter